“In 1857, at the age of 28, a man from Sangamon County, IL, named Alexander Conley Bondurant came to Polk County and made a claim to 320 acres in the southwest of Franklin Township.” This sentence, found near the beginning of a story map created by graduate students in a UI Humanities Lab course, introduces an early Iowa pioneer. It also introduces the town that bears his name, a nineteenth-century prairie settlement that is now the second fastest growing city in the state.

The class “Bioregionalism in History, Theory, and Practice” was taught this fall by Eric Gidal, a professor in the Department of English, whose current research is in environmental humanities. Through the IISC’s yearlong partnership with Bondurant, the 12 students in Gidal’s class worked with the Bondurant Historical Society to research the community’s origins and early years of development. Simultaneously, they read widely in the ecology, politics, and culture of placemaking. The readings focused on indigenous ways of knowing, such as Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants by Robin Wall Kimmerer, and the way early transit systems connected places and made townships viable, such as Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West by William Cronon.

Understanding the Past to Move Forward

“My goals for the class were to help the students develop valuable research skills, gain experience in collaborative, cross-disciplinary production, and develop expertise in publicly engaged scholarship," says Gidal. "I wanted to introduce students to a rich body of literature in bioregionalism and critical infrastructure studies, but to do so in the context of public service. By pairing aspirational readings in environmental consciousness and creative place-making with projects that address the goals of a particular community, the students and I could gain insight into both, particularly when the match was not perfect.”

Early in the semester, Gidal took two trips to Bondurant. The first was to meet with the Bondurant Historical Society leaders, including Deb Harwood and Jan Johnson, who gave him a tour of the central downtown and some of its oldest homes and structures. The other was with his students who joined a larger IISC visit to Bondurant during which city partners provided a tour highlighting new commercial and residential developments, including a large Amazon Fulfillment Warehouse that opened in 2020.

“They were totally different tours,” says Gidal, who was surprised that in a relatively small place no sites were repeated between the two trips. While one focused on the community’s past and included the site of A.C. Bondurant’s original home that had been lost to fire, the other highlighted the present and future.

The question of how to hold on to and remember the past while moving into the future was at the heart of the students’ work. “The town is changing so quickly,” says Harwood, “but you really need to know where we’ve come from to understand where we are today and where we’re headed.”

"Hometown Feel"

The students were tasked with developing user-friend materials for the volunteer citizen group, which formed about four years ago. They divided their research projects into three areas: creating a story map and walking tour of downtown Bondurant; researching specific older buildings of historic significance; and creating teaching materials for upper-elementary school students.

Central to Bondurant’s current growth is its commitment to a “hometown feel,” a phrase used often by its leadership team to describe the sense of place it hopes to maintain. Considering what this phrase means at the personal and community levels came up in many class discussions during the semester. “Questions of home are everywhere in the literature of bioregionalism, from Wendell Berry and bell hooks to Gary Snyder and Robin Wall Kimmerer. In the case of Bondurant, we explored the enormous roles of commercial, agricultural, and transport systems in shaping the city’s history, as well as the longer indigenous history of the region, yet we also came to appreciate the importance of individual acts of imagination, philanthropy, and civic engagement that help to create a sense of place.”

Sophia McLaughlin, who is working toward an MFA in choreography in the Department of Dance, wondered how one finds home in a new place and in the current moment as opposed to in a more nostalgic past. When she drove into Bondurant in the fall, she was struck by the contrast of the mammoth Amazon building, which she could see out of one side of the car window, as compared to old clapboard farmhouses that whizzed by on the other side.

“They’re so close together,” she says. “It really put into perspective the changes happening there.”

Another reminder of old and new Bondurant and the scale and speed of the two came during a visit she made to a small pie shop that’s located in the downtown business district. It was just before Thanksgiving, and they’d been hired by Amazon to make pies for the warehouse’s employees—5,000 pies!

Embodied Mapping and an Imagined Interior

Each student was encouraged to use their own scholarly interests as much as possible in the individual projects they created. McLaughlin, who brings her undergraduate studies in botany into her current study of choreography, created an “embodied map”—a walking tour of downtown that includes invitations to look at some of the native plants growing along the Chichaqua Valley Trail. Her map also encourages walkers to get close to the towering grain siloes that stand in the middle of town “in order to understand the scale of production.”

Tegan Daly, another student in the class who is working on an MFA from the Center for the Book, will create a paper map version from McLaughlin’s work. These will be available at the Bondurant Public Library. Harwood says the map has inspired the historical society to consider creating digital tours that are accessible by phone. “The students’ work has spurred us on to think about a cemetery tour and other information we can share,” she says, emphasizing how pleased she and other group members are with the students’ work.

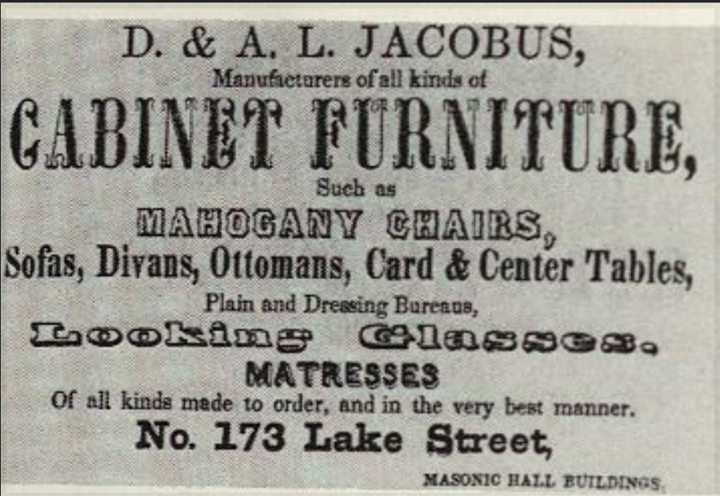

Adelina Pineda-Canganelli, a first-year PhD student in English, produced a conjectural study as to what the inside of A.C. Bondurant’s home might have contained. There are only two existing photos of the outside of the house, which was built in the mid-1850s and burned down in 1917. Pineda-Canganelli brought her interest in the aesthetics of the Victorian era to bear on a project that entailed heavy archival research. In the essay she wrote for the class, she asks, “How does one reconstruct an interior lost to time? How can we look back across nearly 200 years to envision the careful choices made by an enterprising pioneer and his family? What choices were available to a modestly wealthy Midwesterner of the 1850s?”

She found her answers by looking through catalogues of materials available from crafts people in Chicago from the time the house was built. Because Bondurant wasn’t on the railroad until 1892, housing supplies were likely purchased in Chicago and transported by wagon to central Iowa. Everything from cabinets to chairs were available in easy-to-assemble pieces that Pineda-Canganelli says were like the Ikea of the day.

Applying the Humanities

She and other students found parallels between the emerging township on the newly plowed prairie of the mid- to late-1800s and Bondurant’s current boom. The city’s first general store was built in 1884, providing rural inhabitants with everything from textiles and hardware to food they were unable to grow themselves. Its role was not dissimilar to that of contemporary Amazon.

The pairing of theoretical readings with a community partner made the class both appealing and anomalous. Humanities graduate students are rarely asked to write for non-academic audiences. But this was the appeal to Pineda-Canganelli: “I’m interested in how the humanities can be useful. How can I recontextualize all of this dense reading with ways of helping people and being part of communities?”

The class is part of Humanities for the Public Good (HPG), a new collaborative, practice-based graduate certificate currently in development and funded by a major grant from the Mellon Foundation. This semester, IISC worked with another HPG Humanities Lab that looked at issues of language justice in Dubuque. A goal of the labs is to create spaces for cross-disciplinary learning.

“It's great to be in a room with people who are from different departments,” notes McLaughlin. “We get so in our bubbles in our departments. [In this class], the way ideas were presented by my fellow students was really inspiring, and I gained a lot by learning about their research.”

The story map and other materials can be found on the IISC website here. As other UI students work on projects in Bondurant during the spring semester, these materials can provide a foundational reminder of the city’s roots.